Pastor Andy Stanley’s influence and standing in North American evangelicalism are a matter of public record, but where he excels and, by his admission, is most passionate, is in the area of communication. I believe that part of the effectiveness of his approach to preaching is that it shares similarities to well-known homiletical approaches. These similarities may not always be obvious because Stanley’s writing about preaching (or as he prefers, “communicating”) is non-technical and jargon-free.

Nevertheless, a close analysis of the model he espouses uncovers parallels to other influential preaching models, and specifically, those who are familiar with the homiletical methods of Broadus, Craddock, or Robinson will find in Stanley’s approach an additional sermonic tool that will be easy for them to understand and use.

This article is republished from Preaching Magazine. To view the original article, click here .

The Message Map

Stanley’s process for sermon development is known as a message map and is summarized into seven steps listed below.

• Determine your goal. You must first determine your specific goal for the sermon. For Stanley, the goal should be to teach people how to live a life that reflects the values, principles, and truths of the Bible.

• Pick a point. Picking a point helps you end up where you want to go. The sermon should have one point, one specific, short, and simple statement that summarizes the entire message. This point is also called the “sticky statement” because it should be memorable and stick with the listener long after the sermon is over.

• Create a map . Creating a map for your sermon does more than just collect points related to a topic—it leads the people to a specific destination. Another term Stanley uses for this step is “relational outline” because this type of outline builds around the relationship between you (the preacher), your audience, and God.

I have used bold print to identify how the parts of the map function sermonically.

• ME (Orientation) – This is where you explain who you are and what you are about; it is your introduction . You are orienting the audience to yourself and the question/problem/issue with which you are struggling.

• WE (Identification) – This is where you find common ground—it is not merely what I am thinking or feeling but what WE are thinking and feeling together. If the ME (Orientation) is what gets their attention, then the WE (Identification) is where one raises the need and engages the audience, and thus it is a continuation of the introduction .

• GOD (Illumination) – This takes the common ground and applies a biblical principle to it. It takes the need expressed in the WE (Identification) section and gives it a solution. The GOD (Illumination) section is where exposition of the biblical text happens. The sticky statement can be placed at the beginning or the end of this section. The sticky statement is the sermons thesis The GOD (Illumination) part either elaborates on the sticky statement or leads up to it.

• YOU (Application) – This is the application segment. “What are YOU going to do about what you just heard?” The challenge is communicated at a personal level.

• WE (Inspiration) – This is the place where you cast a common vision as a WE (Inspiration) (i.e., corporate vision casting). It also serves as part of the conclusion that describes for the audience what it should look like in their lives when the listener has arrived at the destination.

Steps four through six have to do with delivery or what Stanley refers to as presentation.

• Internalize the message. You should know how to get to the destination of your message and Stanley recommends you preach without notes.

• Engage your audience. Engage your audience on an emotional level by showing them how the truth of the Bible impacts a real need in their lives.

• Find your voice. When both you and your audience listen to what you are saying, they should be able to recognize that it is you. You need to find what makes your speaking uniquely you and use it.

• Find some traction. Stanley believes that to keep the audience interested, one must answer the following four questions:

1. What do they need to know?

2. Why do they need to know it?

3. What do they need to do?

4. Why do they need to do it?

These four questions can serve as a guide for how much information (or exposition ) and how much application should be provided in the message.

With a careful look at the steps outlined above, it becomes clear that Stanley, like other masters of communication before him, stresses the need to know your audience , identify your goal , and write a thesis around which to develop the message.

Finding the Homiletical Wisdom in the Message Map

When one compares Stanley’s model with other well-known homiletical approaches, it becomes obvious how Stanley’s message map shares relevant features from each of them. To be clear, I am not claiming that Stanley has intentionally borrowed from these other approaches, rather I am saying that Stanley’s message map is similar enough in places to these other well-established homiletical models, and thus its effectiveness can be more easily understood and utilized by those familiar with the other approaches.

I have placed them in this order due to the way Stanley arranges his ideas in sermon development. The concepts in Stanley’s message map are in bold print.

Haddon Robinson’s Big Idea and Andy Stanley’s Sticky Statement

Haddon Robinson championed the concept of sermons that are built around and communicate one big idea. The idea – he calls it the “Homiletical Idea” or “Big Idea” – will be the basis for an expository sermon because the principle it contains is derived from the exegetical idea of the passage. Stanley’s “ pick a point ” and “ sticky statement ” are conceptually identical to the Big Idea philosophy that Robinson espouses.

Like Robinson’s use of the exegetical idea as the basis for the homiletical idea, so too Stanley’s sticky statement is based on the topic of the biblical passage under consideration. Further, both approaches to sermon development stress the importance of beginning with one point or idea and developing the sermon around it. Nothing should get into the sermon that does not help to get that one point across.

The Use of Induction in Fred Craddock and Andy Stanley Sermon Forms

Of course, no discussion of inductive preaching would be complete without considering Fred Craddock’s inductive homiletic. No other modern homiletician has been as influential as Craddock when it comes to thinking about the role of the listener in the preparation of the sermon.

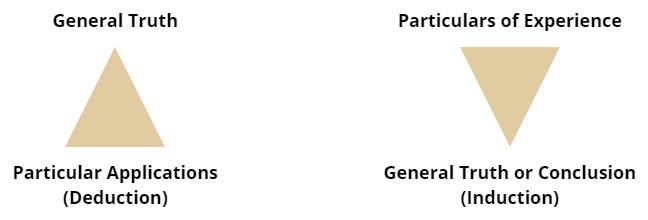

The traditional deductive sermon that announced its thesis and then proceeded to elaborate on it failed, according to Craddock, because it did not reason in a way that mirrors how people actually learn and experience life. Instead, he claimed, people have a variety of experiences and from these draw their conclusions about what is real and true. Craddock represents the differences between a deductive and an inductive approach this way:

Now note how the message map shares the strategies of an inductive approach to preaching. Specifically, it is semi-inductive. The first half of the message map (ME, WE) moves inductively – the preachers introduce themselves by orienting the audience to their perspective on an identified issue/problem/question with which they share common ground with the listener. It begins where the person is; it attempts to solve a felt need that the listener has; and it determines how much information will be shared, based on how best to engage the listener.

Once the preacher reaches the GOD (Illumination) part of the sermon, it becomes increasingly deductive as the sticky statement is revealed and the YOU (Application) and WE (Inspiration) are applications of that statement. Unlike Craddock – who often preferred to leave the application to the discretion of the listener – Stanley feels it is important that the sermon provides personal and practical guidance about how to apply the sermon’s message. While the YOU (Application) can include some rhetorical questions, there is a forceful challenge to respond to the sticky statement of the message, and the WE (Inspiration) provides possible scenarios for the listeners to learn from and follow.

The semi-inductive movement in the message map can be represented in the following way:

The semi-inductive nature of the message map is also similar to Haddon Robinson’s “inductive-deductive arrangement” which he discusses in chapter six of his Biblical Preaching.

John Broadus’ Functional Elements and Andy Stanley’s Relational Outline

John Broadus taught that preaching should contain the following functional elements: explanation, application, argumentation, and illustration. A brief definition of each element is offered below, as well as how these functional elements work in Stanley’s relational outline. Stanley’s terms will be boldfaced.

• Explanation. The passage needs to be explained to be understood or not misunderstood. Broadus warned of the danger of going into great detail in a way that could confuse or bore people. In the message map, it is in the GOD (Illumination) section that Stanley teaches that the preacher should apply a biblical principle to the common ground identified in the first WE (Identification) . Like Broadus, Stanley warns about overwhelming the audience with too much information and stresses that presentation and application must be given priority. Stanley contends that information is only enough if the audience is already interested in the issue or the information is very engaging. If you listen to Stanley’s messages, you can hear how carefully he lays out the meaning of the passage he is preaching over, but he does so with a sense of purpose (speaking to the common ground) and movement, leading the audience to the sticky statement or elaborating on the sticky statement.

It is also worth noting how much explanation can be done when following Stanley’s advice for the reading of scripture:

1. Have the audience turn to one passage only.

2. Don’t read long sections without a comment

3. Highlight and explain the odd words or phrases.

4. Voice your own frustrations and skepticism about the passage.

• Argumentation. Broadus believed that it was necessary to provide an argument for the truth of the ideas that had been explained. In Stanley’s case, the argumentation will likely appear in the GOD (Illumination) section as part of the explanation.

• Application. Broadus asserted that the application was the main thing to be done. In the message map, the YOU (Application) is where application occurs. The audience is challenged to respond personally to what they have been told in the GOD (Illumination) part (especially the sticky statement).

• Illustration. Broadus uses the etymology of the word illustrate to explain it. “To illustrate…is to throw light upon a subject.” He stresses how important it is to make truth “interesting and attractive by expressing it in transparent words and using it in revealing metaphor and story and picture.” While Stanley does not treat illustration as a separate element in his map, it does belong in the GOD (Illumination) section, along with the explanation and argumentation.

Stanley does not use the same jargon as Broadus to describe the functional elements in the sermon. However, the concepts of explanation, argumentation, application, and illustration can be seen “functioning” in his message map.

My study of these three master communicators has led me to believe that there are even more conceptual similarities in their approach to preaching than this article has room to address.

The following diagram shows the similarities between Broadus, Robinson, and Stanley that I have discovered while studying and teaching these approaches side by side:

But is it Expository Preaching?

There has been a great deal of debate about whether Andy Stanley is an expository preacher. He is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary, a school known for its strong commitment to Bible exposition, but in interviews, he has spoken disparagingly of verse-by-verse preaching (he is not a fan of preaching with points either). Many took his comments to mean that his manner of preaching is not, in fact, expository.

It is not my intention to defend Stanley’s comments about verse-by-verse preaching, but instead to simply point out that the message map reveals a strong commitment to the exposition of the text. It’s simply that the text in question and the amount of time given to it are based on the needs of the audience, not the information the preacher has about the text. There is nothing in this approach that undermines or leads to the neglect of Bible exposition; it simply focuses the exposition.

Stanley has said that he thinks the preacher should “teach less material in greater depth,” and anyone who has listened to his sermons knows he does drill down on what a text means as he elaborates on or works toward the sticky statement. Indeed, unless one insists that verse-by-verse preaching is the only way to do expository preaching, then what Stanley has done is provide another highly effective sermon form for communicating the ideas of the Bible in an accurate and applicable way, and this is true whether or not Stanley refers to himself as an expository preacher.

Andy Stanley’s gifts as a communicator are widely recognized, and part of that success is due to his use of an extremely effective approach to creating sermons. The Message Map shares many features with other well-established homiletical approaches. The seasoned preacher who has been trained in one or more of them will find Stanley’s message map easy to understand and use. Stanley shows that one can be committed to the best practices in homiletical theory, exposition, and audience need. What else could a preacher want but to communicate in a way that leads to life change?

Want more ThoughtHub content?

Join the 3000+ people who receive our newsletter.

*ThoughtHub is provided by SAGU, a private Christian university offering more than 60 Christ-centered academic programs – associates, bachelor’s and master’s and doctorate degrees in liberal arts and bible and church ministries.